Episode Transcript

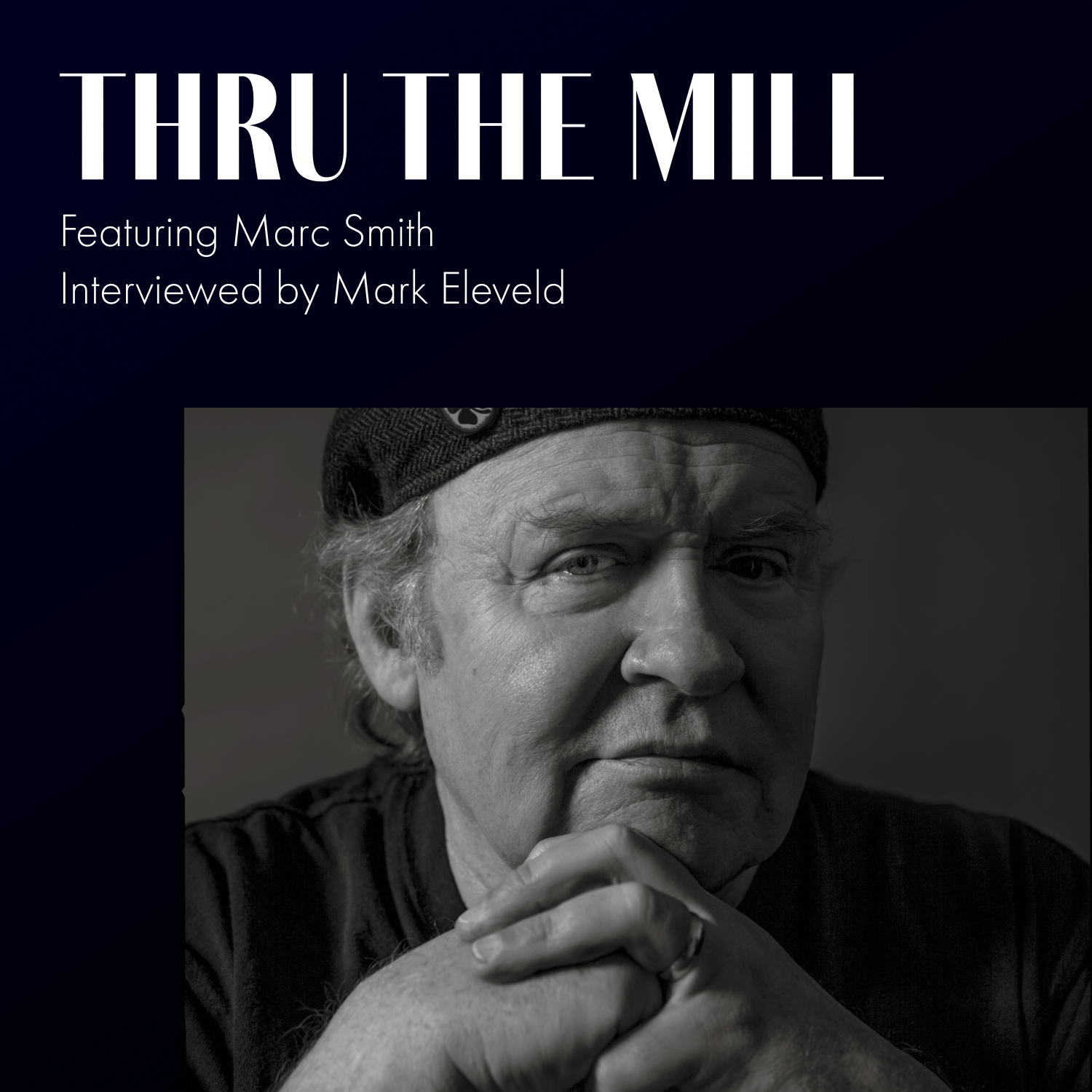

[00:00:10] Speaker A: Welcome to through the Mill, the poetry Slam podcast on the origins of poetry Slam. My name is Mark Elleveld. I'm the editor of the spoken word revolution series. And I'm here, as always, with Mark Smith, who's really the subject of our podcast.

[00:00:25] Speaker B: And leave it right there. Stop all the other stuff.

[00:00:28] Speaker A: Mark is the founder of the poetry slash.

[00:00:30] Speaker B: That's good.

[00:00:31] Speaker A: We'll take that one. Yeah, I'll take Chicago icon. The poets and writers magazine called you such.

[00:00:36] Speaker B: Yeah, years ago. Years ago, yeah. So that's good. I did start the slam, that's for sure.

[00:00:42] Speaker A: Started the poetry.

[00:00:43] Speaker B: So who else is here with us.

[00:00:45] Speaker A: Is at the table with us this week?

[00:00:47] Speaker B: Mark? Yes.

[00:00:48] Speaker A: The famous, the famous Bridgeport poet Billy Lombardo. Hi.

[00:00:53] Speaker B: Yay. There you go.

[00:00:55] Speaker A: And so, so, Billy, this is a podcast. Mark is leaving for tours France again in about two days. I'm saying, I'm telling everybody he's spending like six months out of the year overseas.

[00:01:07] Speaker B: What a lie.

[00:01:08] Speaker A: I think that's true. No, it's got to be pretty close. But it sounds cool when you say it anyhow.

[00:01:12] Speaker B: A few months.

[00:01:13] Speaker A: Yeah. Well, you're leaving. You just got back and you're going.

[00:01:15] Speaker B: I just got back. I'm going. And then I'm going again in November. So maybe, maybe.

[00:01:21] Speaker A: And this is their big event in tours, France.

[00:01:23] Speaker B: This is their big trophy. Trophy something. It's their adult national slam.

[00:01:31] Speaker A: It's their trophy something. Adult national slam. We're gonna fact check that with our.

[00:01:35] Speaker C: Crew after this is all done. Sounds official.

[00:01:39] Speaker A: But the reason we're doing the podcast in part, is Mark came back from overseas and a lot of the younger, well, a lot of the audience want to know the origin and the roots of the poetry slam.

[00:01:49] Speaker B: Yeah, mostly. Mostly younger people. Yeah. Coming into it.

[00:01:53] Speaker A: Yeah, yeah. And so we've been doing kind of a chronological and kind of putting the pieces how this all evolved. We went back to Mark being born on the southeast side of Chicago, the first book he read, going to college for a little bit, and taking it all through his performance, upbringing and such. But there's two strands that kind of stick out, and one of them is, in part why you're here, that the slam caters to a whole diverse set of writers and artists. It's not the poetry slam where you go in and it's only poetry. There's nothing wrong with that, but that's not what this is. And then we're at the point in our timeline where Osaka came up at the last podcast, and that's when Mark said that we gotta get Billy in here to start talking about Osaka and the poetry slam. Kind of raising its roots in Chicago as part of the second sister.

[00:02:45] Speaker B: And that. Correct me if I'm wrong, that's where you got. That's where I met you. I used to go to the deja vu, which would. Dave Gemolo, the owner of Green Mill, owned the deja vu, and he had a jazz jam session. I used to go there after the Green Mill show just to chill out. And I would get up on the stage and I'd do a poem with the band. I was in my promoting thing, promoting the poem for Osaka competition, which was a citywide competition that Lois Weisberg, commissioner of cultural affairs in Chicago, I was working with her. David Hernandez had introduced me to her. We were coming up with a big festival for neutral turf. We wanted to be involved somehow. And she suggested to have a citywide competition, performance poetry competition, to get a champion that would go to Osaka, Japan, because Osaka was a sister city, and they had a big festival that we were working together in Chicago, and I'm in the deja vu.

[00:03:51] Speaker A: Well, a couple real quick things. So the neutral turf would mean that it's like all these different kind of organizers and different opinions on poets come together.

[00:03:59] Speaker B: Yes.

Made the name neutral turf, because these factions were the poet game. Jealous. They were all little, small circles of poets, and they're jealous of each other. Neutral turf was the name we came up with to try to bring them all together for an event. We had done one, I think, at a blues club, at the Blues Club on Belmont the year before, which was kind of successful. But this was a bigger thing, where the festival was going to be at Navy Pier. Before. Navy Pier was the big tourist attraction, but it was a big event at Navy Pier. And that's where we were going to have our final competition for the poem for Osaka.

[00:04:44] Speaker A: And I want to mention, because you brought him up, the unofficial poet laureate of Chicago, David Hernandez, who's passed, but that was the tag he always gave himself, which eventually was when we were talking about poet laureates. And our friend Avery young is the first. I was hoping. I talked to them when they were doing. I was hoping they would make David. The first unofficial, posthumous name is something we'll return to in the podcast. David Hernandez.

[00:05:09] Speaker B: I absolutely have to. And, you know, he was. And he introduced me to Lois Weisberg because he knew them. He was an outsider just like me. You know, they were the neutral. The guild, the feminist Writers Guild, which became guild complex, organized neutral turf. And they were the only association that I know of, besides the green mill, that was open to anybody coming in there. It was. All the outsiders were there. And so he introduced me to her.

[00:05:40] Speaker A: And is it fair to say when Lois Weisberg, the arts commissioner of Chicago, who worked with Daley, when she kind of gave her stamp to this, this was a very official cool.

[00:05:52] Speaker B: I felt under pressure that I better do something good.

So I went. We put the word out to all the different. To everybody in Chicago. Each group, little faction, could send their own champion to a competition.

[00:06:07] Speaker C: And there was stuff every night of the week. There was two and three places that had poetry. You could do poetry every night of the week.

[00:06:14] Speaker B: Yeah. Yeah. So Billy's there at the deja vu, and I announce it from the stage. He comes up afterwards and am I got it right?

[00:06:23] Speaker C: Yeah, yeah. And I introduced myself to you. I had been. I think I had been at the green mill for a couple of Sunday night slams and hadn't read anything there and was a little intimidated by it. But I said, can I get in on this? You know?

[00:06:36] Speaker A: And what year would this be?

[00:06:37] Speaker C: This would have been 88, I think. The summer of. Maybe. The summer of 88.

[00:06:42] Speaker B: Summer. Spring, maybe.

[00:06:43] Speaker C: Yeah. And I remember the poem had to be 80 line. 80 or fewer lines. And a tree had to make a cameo in it, because the winner would go out to Osaka, Japan, and present it at some horticultural festival.

[00:06:57] Speaker B: The whole festival, the bigger, the big city, sister cities collaboration with Chicago was about horticulture and that. And Mayor Daley was big on freeze at the time. The three. The three things in there. And now that you say the 80 lines, that probably was me, because I didn't want those poems to be too long.

That was probably one of my rules.

[00:07:20] Speaker A: 80 lines come out to three minutes about. Or less.

[00:07:22] Speaker B: No less.

[00:07:23] Speaker C: I don't know, it just seems. It seems like a long poem still to me, 80 lines. But I remember I was with the buddy of mine, Maddie Vaccarallo, because he was to take me to. He would take me to deja vu all the time. And I ran into you, and then I just went right. I just went right home and started writing a poem. And I just remembered a specific tree on my paper route. Paper route 32 that I always used to look through. There's like a street light behind it. And the tree, the shine of the light, would just, like, be the circular shine on the trees, and I just would be mesmerized by it as a kid. Yeah. This is called the last tree on paper route 32.

I meet the tree. Well, into the first autumn of my paper route in front of Mister Johnson's house, on a square of earth that is long since outgrown, the light of the street lamp behind the leafless tree stretches into the street. And in the dark of morning, when I stand where the sewers sign their names on the once wet cement and become a triangle with house and tree, the street light flows through the nave of the branches like a low moon.

I stop every day to see the tree whose branches in winter leg like spiders and cradle like nests, and sometimes are just branches with street lamp behind.

Spring brings flowers and brown branches to the moon, takes black and shine in the circle from the low moon.

Summer brings leaves and green and takes the low moon until autumn, who only takes withers and blackens and fells. And when I squint and lose the pole, the light becomes a low moon and all of the thin fingers of the tree ripple around the light, black and shining, and spread its glow like how a dark, quiet river echoes the moon when a little boy's pebble is well thrown.

That's the last tree on paper. L 32.

[00:09:35] Speaker A: Japan was nice.

[00:09:36] Speaker C: Yeah, Japan. I didn't end up going to Japan.

[00:09:39] Speaker B: To go to Japan.

[00:09:40] Speaker A: You said we were getting a winner here, Mark.

[00:09:42] Speaker C: For years, Mark would introduce me for my father's Day feature at the. At the green mill. He'd introduced me by saying I was at fifth place in it.

In my memory, it was actually third. So I would correct him every Sunday.

[00:09:57] Speaker B: Where did you compete to get in the semifinals?

[00:10:00] Speaker C: So I competed at the Green mill because I remember Billy Cosentini, who I went to grammar school with. He wrote a terrible poem about it. But I also. Rand, you were the representative of the green mill? I was the representative of the Green mill.

[00:10:17] Speaker B: Oh, okay.

[00:10:17] Speaker C: I'm not positive it was. There was another place on Belmont around the why not cafe seminary, somewhere around there that it might have been at. I think that's what. Right. I wasn't the representative of the green Mill. I was representative of one of these other people.

[00:10:30] Speaker B: Why not? But then you also tell us about that.

[00:10:35] Speaker C: So I used to work on 11th in Michigan at a place called Clancy's commissary. And there was a bar not too far from there. It was just a cop bar. And so I hosted my own poem for Osaka segment there at the cop bar. Yeah. And Mark has a better memory of this here because I said, I think I brought index cards. I went to Walgreens, got some index cards for it, for them to write their.

[00:11:03] Speaker B: And the cops would not use the index cards. They would only hold up their hands.

[00:11:10] Speaker C: They were just like, cut out the middle man.

[00:11:13] Speaker B: Cops were the judge.

[00:11:14] Speaker C: Ten fingers.

[00:11:16] Speaker B: Cops were the judge.

Class. That was great. It was well attended, too.

Who won that? Do you remember?

[00:11:24] Speaker C: I have no idea who ran it. I have no idea who ran it.

[00:11:28] Speaker A: This is a little insider, but. Billy.

[00:11:31] Speaker C: Billy Constantini. Yeah.

[00:11:33] Speaker A: He's a friend of yours?

[00:11:34] Speaker C: He was. Friend is generous.

I went to grammar school with him.

[00:11:40] Speaker A: Equate. Is he not in the legendary shtick at the Green Mountain?

[00:11:44] Speaker B: He's in the dumb riot. The dumb slam. Dumb song. The dumb song.

[00:11:50] Speaker C: Because he got negative infinity for.

[00:11:52] Speaker B: He was the first person to get negative infinity for a poem where he was.

Billy. I'm sorry. I'm not.

Should I say he was, like, diddling the tree?

[00:12:07] Speaker A: That's the thing. He tried to put his little thing.

[00:12:09] Speaker B: Into every nasty knot of an old oak tree. Sorry, Billy.

[00:12:14] Speaker A: He's been immortalized.

[00:12:16] Speaker C: He was stepped in the green mill one time, and he's like, now if.

[00:12:21] Speaker A: We could pull back just a little bit. So that's your entry into the green mill and mark and poetry slam by way of Osaka, Japan. But what's your every. I've only known you as Bridgeport Billy Lombardo. So what's your background prior to the green mill?

[00:12:35] Speaker C: Well, prior to that, I just. I mean, I felt like I was. I felt like I was a writer, but there was no empirical data to back that up. I had a couple situations where I felt like, wow. I just felt sort of the power of writing and nailing, languaging something that someone else could read and feel exactly what I felt. And I had that experience a couple of times. And I thought, well, I'm just a writer. And that was. The green mill was the place when. I mean, I didn't realize that I was in on it so early, because it had only been at the green mill, I think, since 87.

[00:13:13] Speaker B: Right? It started at 80. 86 Deppie High started 84.

We were talking before we started, you know, this recording that when I start thinking back on it, it seems like those early years were a decade, but it was. So much happened within a period of three years. So much, it just exploded. And so you have the same feeling, like, wow.

[00:13:39] Speaker C: I just felt it was this. I mean, Patricia Smith was there, and.

[00:13:42] Speaker A: She'S the one that won the si.

[00:13:43] Speaker C: Right. She ended up winning it, but she was on stage the first time, and I was weeping, and then I was like, what the fuck? This is poetry.

[00:13:52] Speaker A: Right? Right.

[00:13:53] Speaker C: And sin solace and Dave Kadesky and Lisa Buscani and Carrie Lovestad.

And then a couple just crazies, too, that were there. There were definitely some crazy people, too, there on this show.

[00:14:05] Speaker A: Of course.

[00:14:06] Speaker B: Of course.

[00:14:08] Speaker A: So you're a newly again suffering white Sox fan. Is that a fair way of saying.

[00:14:12] Speaker C: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

[00:14:14] Speaker A: And then where did you go to school?

[00:14:16] Speaker C: So I went to Chicago thing. Yeah. The parish I was at was St. David's on 32nd in Emerald. And then I went to Quigley South High school seminary, and I just wasn't much of a. I wasn't much of a reader, and I certainly wasn't much of a writer, but I had, like I said, I had already always felt I had a little something. I felt like I was a kind of a writer. So, you know, an early teacher had written my cub reporter at the top of a paper or something. I wrote, and I was like, what's a cub reporter?

And I was like, is she making fun of me because I like the White Sox?

[00:14:53] Speaker A: Easy target.

[00:14:54] Speaker C: Yeah.

But the thing that happened at the.

[00:14:57] Speaker A: Green mill was, did you go to college?

[00:14:59] Speaker C: I went to a seminary for college also. Yeah. And wrote a little bit there also. Really. It wasn't seriously writing for anything until I was the green Mill. And there was this stage. It was every. Every Sunday night there was a place to go and to read poetry. So I started writing it, and I had some, what I thought of as success there, because, you know, people were smoking in the. This was back in the days of smoking in bars and drinking, and it was still really new to the scene, to the green mill then. So people still.

[00:15:37] Speaker B: They didn't have to be respectful, right? Yeah, you had to shut them up. And that's probably what you're saying.

[00:15:42] Speaker C: If you quieted them down, you could just feel it, that something. Everybody would just start listening. And it was, oh, if that happened once, you just wanted to happen every minute of your life.

[00:15:53] Speaker A: Did you start noticing particular lines or images that would quiet them down?

[00:15:58] Speaker C: Yeah, but I would also. And that was when I was just most sort of vulnerable and most honest. But there were also times, and I think this happened to a lot of people there, where you just went there and you started writing something that, oh, this was going to be. This was going to do well at the green mill, and if you throw the f word in there, it was going to do well. And then you just made a bunch of mistakes, because I would be like, all right, I'm going to write one that's going to just like. That's just going to knock him dead. And then I would go there the next Sunday after reading it, Mark would say, hey, hey, don't read that one poem about the guy pissing in the urinal. Don't read that poem. And I'll be like, okay, not going to read that one ever again.

So he sort of.

[00:16:39] Speaker A: Was he right?

[00:16:39] Speaker C: Coaching? Yes, absolutely. He just sort of coached me through it, and it just. It takes a while, and then you sort of, you find your way through, and then you find, this is the stuff that's going to work, and this is the stuff that's, that's not going to work, and this is just more authentic or whatever. And those are the, those are the things that would, the poems that would happen there where you'd really, you know, you were, you had a better chance of just kind of shutting things down.

[00:17:08] Speaker B: Of your personal life, the things that really, really mattered. You would get the best response. Not the great afterwards.

You would get the great rock the house roar. But the really great moments were where the poem ends. And then there's this silence for a few seconds.

[00:17:30] Speaker C: Yeah, yeah, yeah. And I felt one of the things that, the question mark, too, is I didn't have the language for this then, because I never studied writing or anything.

It was this pieces for me that had a range of emotion. So there would be some funny moments and there'd be a couple swear words, and then it would just come around at the end to something that landed heavily, and they wrestled. They wrestled with something, I think. And that's one of the things I would say also about the poems that did well there and the poems where you could see that Mark was appreciating it, too, from the sidelines, you know.

[00:18:05] Speaker A: And setting plays a very big role in your writing.

[00:18:07] Speaker C: Yeah.

[00:18:08] Speaker A: You are a Chicago poetical.

[00:18:09] Speaker C: Yeah. Right. And that's. And I wanted to do that. I wanted to be like a Chicago, a Chicago writer. And Mark always. So he would call me Bridgeport Billy, and he would make, he would, in his way of teasing about it, also exalted that place. And we were from similar places and from similar blue collar families, and it sort of exalted the place that I grew up. Nobody really exalted it. You know, the people in it loved being in there, and they protected each other and that kind of thing. But nobody from outside of Bridgeport. Exalted Bridgeport.

[00:18:46] Speaker A: I was at, we talked about, like, mark creating characters in his own audience, and I, because I think I met you probably through Dick Prince.

[00:18:55] Speaker C: Yeah.

[00:18:55] Speaker A: And it was probably the Bridgeport Billy poet.

[00:18:58] Speaker C: Yeah.

[00:18:59] Speaker B: French for the audience was the college, one of the few college professors that loved Islam and came out. He was there. He was the only person who was close to being there as many times.

[00:19:11] Speaker A: As I was from Lewis University. Yeah, he passed away not too long ago. What was the piece at Steppenwolf?

Do you remember that?

[00:19:19] Speaker C: Yeah, I'm pretty sure. So the Steppenwolf, were they doing a.

[00:19:24] Speaker A: Theatric performance of a poetry piece or a play or.

[00:19:27] Speaker C: They were doing.

[00:19:28] Speaker A: So this is the great Seppenwolf Theater.

[00:19:30] Speaker C: In Chicago, and I was on stage with Alex Kotlowitz and Stuart Dyback, and Tony Fitzpatrick gave me that spot. Like, he did stuff for me, like my first radio show. Rick Hogan asked Rick to do something for me.

He gave me a piece of advice early on when my first book came out, he said, I'm just giving you a little piece of advice. He said, don't say no to anybody. You're not in any position to say no to anyone if they're here today. And he said, I don't care if it's a fucking book club. And then finally there was a book club. They called me up at 645, and it started at 07:00. And they said, I know you're right. We're in river Forest or Riverside, and you're right in Forest park. And I was like, I gotta draw the line here, Tony.

[00:20:16] Speaker A: But at the Steppenwolf performance, I bring this up, because when your piece was over, there was kind of a small q and A, and there's a very tall guy. You had a lot of Bridgeport people there, and the Bridgeport guy stood up, and you went to elementary school with him or something, or one of his brothers or something. And he had two questions for you. And question number one was, if you could look at yourself 20 years ago now, would you punch yourself in the face?

And then the second question was, what was your favorite corner in Chicago?

[00:20:49] Speaker C: Yeah.

[00:20:50] Speaker A: Remember that?

[00:20:50] Speaker C: Yeah, I do remember somebody asking something like that.

[00:20:53] Speaker B: Did you punch yourself in the face?

[00:20:55] Speaker C: No. I was like. Like, on the stage of the sepulchral theater. I was, like, ready to come off the stage and punch you in the face.

But I remember my book had just come out of logic of a rose, and I read a piece from that. And I think part of what he was getting at is that I didn't show any signs of doing this kind of thing when I was in high school or grammar school. And it just seemed like, you know, I was with people who had. Who had never read a book, let alone you. Know, let alone write a book, you know? And there was all my friends. I used their. Their names in the book because I knew they were never gonna. They're never gonna read it. And if they did and they saw their name in it, they'd be like, hey, I'm in a book.

[00:21:43] Speaker A: Yeah.

[00:21:43] Speaker C: One of them said, I didn't know what you were. I didn't know you were a book writer.

[00:21:47] Speaker A: I think Jack Kerouac's age.

[00:21:49] Speaker B: Were you writing the short stories before that?

[00:21:51] Speaker C: No, it was after. It was after.

[00:21:56] Speaker A: Logic of the Row is a beautiful.

[00:21:58] Speaker C: Book, Billy, how's your first book?

[00:22:00] Speaker B: One of the.

[00:22:00] Speaker C: That was the first book. And I didn't know anything really about writing, but I realized when I was, that my poetry was. My performance stuff was. Was just highly narrative. And I ran into Stuart Dieback at a lit fest at St. Ignatius, and I introduced myself to him, said I was from Bridgeport. He said, oh, I couldn't help myself. I walked to the old neighborhood today. He said, where'd you live? And I said, I lived above a bakery. And he goes, where? And I said, 33rd and Wallace. And he goes, dressel speak.

And I just. Yeah. And I just felt it was a kind of invitation to write about those places. And he had written in coast of Chicago was out by then, and he had written about Bridgeport. And so I just kind of went back there and just started writing some stories about that place and still kind of kept going to the green mill when there were shorter pieces that I would. That I would write.

[00:22:55] Speaker A: But, yeah, I was with Mark one night talking about my writing or desire, and he said, if you want to read Chicago, read James McManus his novels and Stuart Dieback. I told Stuart that after the fact, when I got to meet him, and he said, mark Smith, this gets to the Chicago icon thing at the poets and writers, because Mark and Stuart were finally on stage together. And Stuart Dybek's the great Chicago coast of Chicago, like you said. Yeah.

[00:23:20] Speaker C: You were on stage with them where?

[00:23:22] Speaker A: For poets and writers. Chicago icon presentation.

[00:23:27] Speaker B: I don't even remember.

[00:23:28] Speaker A: Yeah. And Stuart said, actually, I was talking to Stuart at one of the printers. Rose and Stuart kind of came from back and stood next to me, and we were watching Mark. And he said, mark Smith performs the classic poems. It's. I could watch it for hours, he said. And I used that line at the Chicago icon where it was Stuart and Mark together. And what does Mark not do? He doesn't perform one of the classic pieces that Stuart was waiting for. He does his own original context.

[00:23:56] Speaker B: What the hell would that be?

[00:23:57] Speaker A: That's also a line that Tony Fitzpatrick gave me. He's like, Mark Smith is the most contrarian person I've ever met in my life.

[00:24:03] Speaker B: What the hell was I thinking?

[00:24:05] Speaker A: Can you go through your books now that we've established how you got into the green mill? Kind of go through your books.

[00:24:12] Speaker B: Yeah.

[00:24:12] Speaker A: I mean, once the green mill takes off and you're. You're in.

[00:24:15] Speaker C: Yeah.

[00:24:15] Speaker A: You're gonna.

[00:24:16] Speaker B: You're in. You go to national slams or on a. You. You were at the. The first official team for the national slam in Chicago in 1990, right?

[00:24:26] Speaker C: I wasn't on. I wasn't on the team.

[00:24:27] Speaker B: Wasn't on the team. But you helped organize things, right?

[00:24:31] Speaker C: I was in, yeah.

[00:24:32] Speaker B: You were a major in organizing. We had such a great volunteer group of, like, 2025 people working together, and you were instrumental in those early meetings to make this.

[00:24:46] Speaker C: Make it happen, you know? Yeah, I felt like I was in on it. I felt like. And also the poem for Osaka really seemed to, like, give it this urge forward.

[00:24:57] Speaker B: Also the first word. Someone in the slam world, one got some big thing, and everybody, now everybody's taking note of it, so.

[00:25:08] Speaker C: Yeah, and they just were. I just remember them being. It was so crowded at the Green mill every Sunday and just started going there early just to make sure that you got a seat at the place.

[00:25:20] Speaker A: That's true. I remember Reggie Gibson performing once there, and there was a line out the door with people waiting to get in.

[00:25:25] Speaker C: Yeah.

[00:25:26] Speaker A: Can you take us through your books then? Yeah.

[00:25:28] Speaker C: So logic of a rose came. I started writing those stories right around then.

It was 1997 when I started writing it, because the first day of spring, I took my son there to Bridgeport to kind of, like, urge forth some of these stories from the old neighborhood. This was, like, shortly after the Leonard Clark beating in Bridgeport. And I remember seeing, I went to the bakery, and there was a sign, a piece of paper on the bakery wall that said, this is place where people live. It's not a toilet. Don't piss in the hallway. And I remember showing my son that, and I took him around a couple other places, and we're getting back in the car, and he took me by the hand. He's five years old at the time. And he said, dad, I'm honored that you took me there, that you took me here. And I was like, I don't remember teaching him that word, honor, you know, but somehow he had sort of understood it. So I spent a few years just working on stories that were.

[00:26:27] Speaker A: And for non Chicagoans, Bridgeports, Lithuanian, Italian, Irish. Irish.

[00:26:34] Speaker C: Yeah. And I thought of it just as, I just thought of it as italian because there were like, you know, three or four people living on the other side of me were all Italian. And it surprised me to find out that the Irish were the first that were in the, that were in the neighborhood.

[00:26:48] Speaker A: And the dailies.

[00:26:49] Speaker C: And the dailies were, yeah. 35th and low, and I was 33rd and Wallace.

[00:26:54] Speaker A: And in terms of race issues, which is kind of what you. There's like, there was a crossing line.

[00:26:59] Speaker C: Right, right. Yeah. And, yeah. And it was pretty, I mean, the Eisenhower expressway was pretty much the sort of dividing Eisenhower. Yeah, the Eisenhower expressway.

Yeah. And it was just racially intolerant growing up there, though. It was, there was also, like, a lot of beautiful stuff, and I just felt it was a rich childhood, and that's kind of what the, sort of narrative threads running through, through that book. So it was the logic of a rose. And then you approached me about putting some poems together and you gave the title also, meanwhile, Roxy Morrins.

[00:27:38] Speaker A: Meanwhile, Roxy Mornes. It's a collection of poems and small essays from Em Press. Very handsome picture on the COVID Right, right.

[00:27:46] Speaker C: And then after a while, I went to Warren Wilson in maybe 2007 through 2009, I went to Warren Wilson for my MFA in a low residency writing program there. And three books came out in pretty quick succession. And that was, meanwhile, Roxy Morin's how to hold a woman and the man with two arms. And. Yeah, and that was, and the last two were novels.

Yeah. How to hold a woman is now out as morning will come. And that's a novel and stories. And then the man with two arms is about a perfectly symmetrical, ambidextrous athlete who becomes a switch pitcher, major league switch pitcher.

[00:28:33] Speaker A: We have a fan who called in a question. So in your novel morning will come, which you just mentioned in the acknowledgments you wrote, and Mark Smith, whose stage at the Green Mills uptown poetry slam is pretty much to blame for all of this.

[00:28:48] Speaker C: Ah, good for me.

[00:28:50] Speaker A: How did the slam affect your prose writing? So, because you said that line like when you first saw it, you're like, oh, I didn't know. This is poetry.

[00:28:59] Speaker C: Right? Yeah, yeah. So, I mean, I just was, I had never been moved by poetry like that. And so it introduced me to a lot of different kinds of writing. You know, I'm just, I'm more interested in page poetry now than I've ever been interested because really, an insistence on precision. That was one of the things that also had to be a part of the poem, I think there had to be a love for language in it, and you could see that in Mark. That's one of the things that actually struck me about Mark, too, because I didn't expect him to be a student, like a scholar of language in the way that he was, or as a great a listener as he was. But there would just be, like, times where I would be disappointed in myself because I was just, like, you know, goofing around in the audience and drinking, and I'd watch Mark, who was just, like, attending to every single word, remembering a couple of them afterward and appreciating them and that sort of thing. So one of the things, though, that I felt was really helpful to my writing is that I was always writing for sound. I was always thinking about sound. Even as a teacher, I would tell people, read this thing out loud, read it out loud, read out loud. And I felt like I just didn't have to read my own stuff out loud because I had been doing it so long at the green mill that you were just always reading for sound. And that's one of the things that affected my own writing.

[00:30:26] Speaker A: Award winning writer.

[00:30:30] Speaker B: Wow.

All these years, he never said this to me.

[00:30:33] Speaker C: That's just not true.

[00:30:36] Speaker B: I wouldn't have been so contrary if I would have got a little bit earlier.

But, you know, he does bring up this sonically, you got to be aware what's happening. Paint the picture, you know, the images that get out there. At the time that I. We started the green mill, language, poetry was a big thing, and it was so abstract.

You never would get an image. It wouldn't. You couldn't have anything to hold on to. And everybody who were, you know, most people that, you know, that started to get me high, we're all writers, but it was just this richness, I think you said, this richness of the language, that it just came alive.

And when you didn't make it come alive, the crowd let you know.

It had to be. It had, like you say, it had an effect on them.

[00:31:31] Speaker C: Yeah. It was so clear when something wasn't working on the stage. And the other thing, I think that I started thinking about when I would go on. I had a couple of, like, short, sort of book tours, and I was at a Sunday salon in New York, and I did a piece there that always worked at the Green Mill. It just was a crowd pleaser. It always worked. And I read it in New York, and the crowd just wasn't with me.

So I had this sense that in Chicago, they would be with you until you're a jag off. That's what I'm saying. You know, they would. In New York, you're a jag off until you prove otherwise.

[00:32:14] Speaker B: Well said, billy.

[00:32:16] Speaker A: We're having Tony Fitz on soon. Mark's gonna see if his New York story matches up with Tony's New York story.

[00:32:23] Speaker C: They finally started coming around, like, halfway through, and by then I was like, fuck you.

[00:32:27] Speaker B: Yeah, good.

[00:32:29] Speaker A: True Chicago style goes our New York sponsorship. Thanks, Billy.

Mark, what's it feel like looking at Billy and like, I mean, you've known this because you're good friends for a while, but he's. He's saying that you changed his life.

[00:32:43] Speaker B: You know, Billy's always expressed true, true love and respect for me. It's. It's been a treasure, the whole thing. You know, I make fun of. We make fun of each other constantly, but no, we. We were. We were kindred spirits, right. Right from the start.

[00:33:03] Speaker A: Is Billy a slam poet, or doesn't it matter?

[00:33:06] Speaker B: That word slam poets, a bunch of bullshit, you know? And I. Billy will attest to this. The styles. When. When he was in there at the beginning, every. Everything was different. You couldn't say one. He was a slam poet because he performed, you know, he performed it and he got through to you. He learned performance by watching everybody else. But as far as making the slam is some style or scene or bullshit, you know, any poem, as I've said, it's performed as a slam poem. And if you're. If you're performing your poetry, you're a slam poet.

[00:33:44] Speaker C: And the themes were all. I mean, they were just. There would be times when I would go to the green mill and it would just all be like, this is a particular kind of poem. This is about being. This is about being from where I am. And when I was there, it was just like, there would be just, like, ordinary moments in a day that someone would write a poem about, you know, and Patricia Smith would be there, and she'd write about a tree and can make you cry. And then it was just like, I felt like there was a real depth to poets there, and it wasn't everybody. You know, you can go there and hear some pretty bad poetry every once in a while, you know, Billy Constantino, right?

And sometimes the audience would be like, if it was, you know, I would be in a slam against somebody who had, like, a theater background, and I would feel like my poem was, like, way better than this dude's poem or whatever, but I didn't memorize my poetry as much as these other people. And then someone get up there and they would just like win the crowd over because, because they were more theatrical.

[00:34:48] Speaker B: Performance because the performance was a craft, too. And the goal was always the best possible poem with the best possible performance.

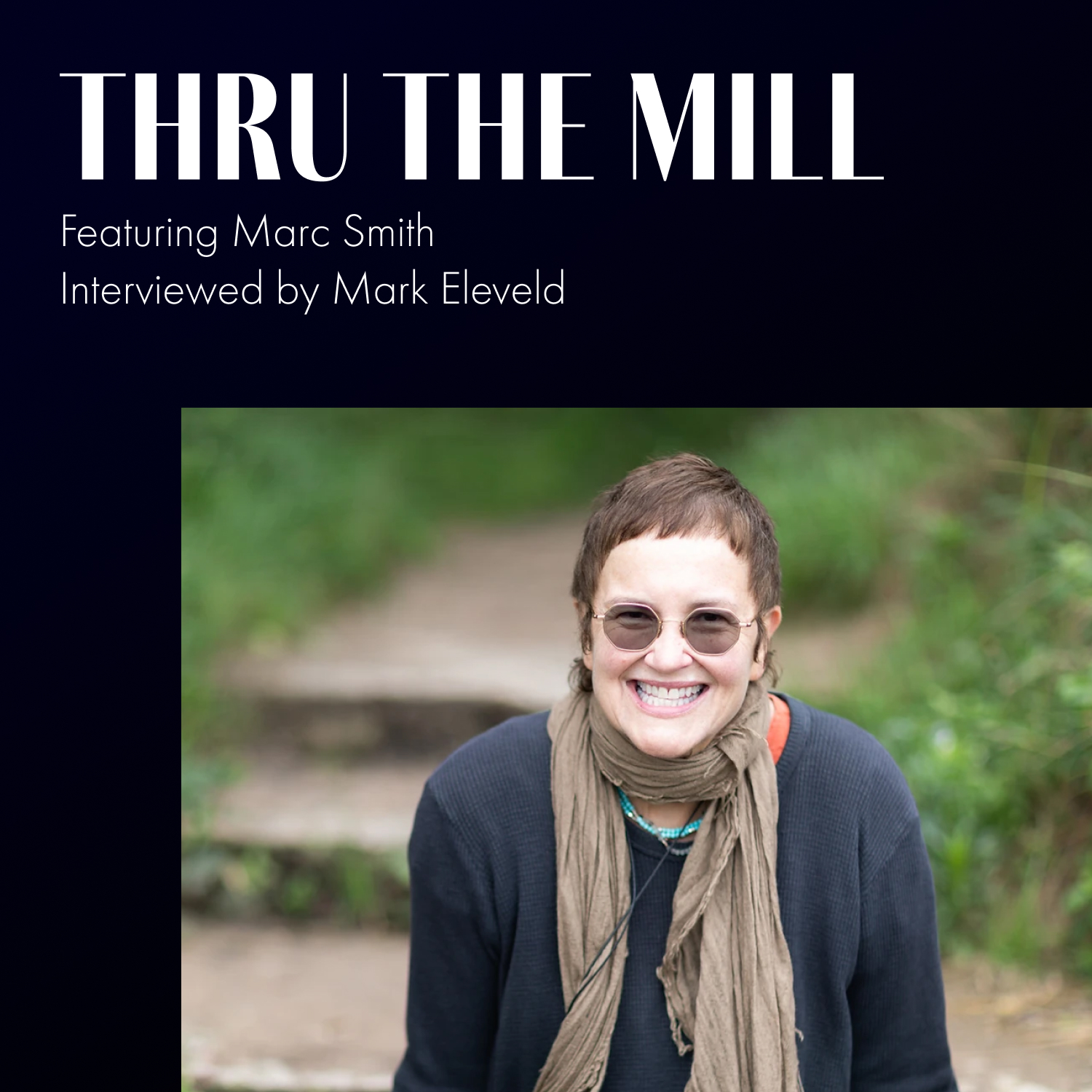

[00:34:58] Speaker A: You've been listening to through the mill, our podcast about the poetry slam. My name is Mark Eliveld. I'm the editor of the spoken word revolution books. Emily Kalvo is here with us. She named the podcast. It's an anthology she's been working on since the early nineties. And we're here with Mark Kelly Smith, the founder of Poetry Slam. We're going to be bringing some podcasts and shows to you to hear the origin stories from a bunch of different poets and a bunch of different organizers. Our director Hugh's over there in the corner. I hope you had a good time and we'll talk to you soon.