Episode Transcript

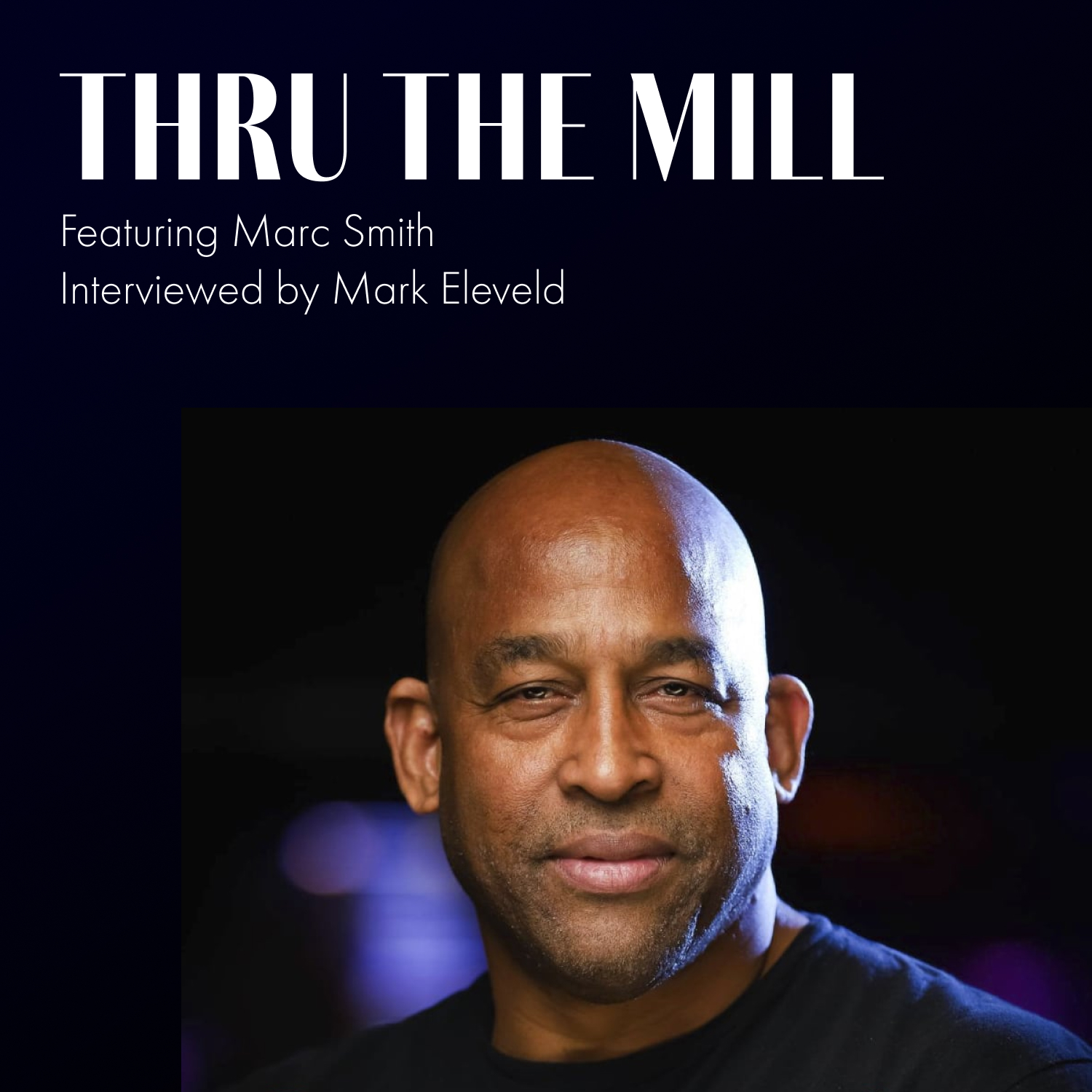

[00:00:05] Speaker A: Welcome to the podcast through the mill. My name is Mark Elavald. I'm the editor of the spoken word revolution books. This is a podcast on the origins of poetry Slam. And as always, we are here with Mark Kelly Smith, the founder of the poetry slam. Hi, Mark.

[00:00:21] Speaker B: Hello. Hello, Mark. And we also have with us Eleanor Fisco.

[00:00:25] Speaker C: I am honored to be here.

[00:00:26] Speaker B: Thank you. Italy. Yeah. It's a pleasure to have her here. Come to Chicago, to the University of Chicago. She's on a scholarship, and she's a slam scholar. Imagine that. In the beginning, the universities hated us, and now they're bringing scholars from Italy to research and study slam. But while she's also here, we hooked her up with the one poetic voice stuff, which we were talking about previously, you know, the international scene where we started working together with the two languages going at tandem.

[00:01:03] Speaker A: Yeah. So there's a lot to get into. I mean. Yeah.

[00:01:05] Speaker B: So we got an example this week.

[00:01:07] Speaker A: That's awesome. Okay, so when we. We started this podcast, in part because Mark was in tours, France, Brazil, and someplace else overseas.

[00:01:16] Speaker B: Portugal.

[00:01:17] Speaker A: Portugal, that's right. With your friend who's the organizer in Portugal. Lille. Lille. And so when he came back, he said he's talked to a lot of people over there, and there was not, like, one centered place to go to on the worldwide web or the Internet for how did this stuff begin? How did it branch out? And all those different stories that go with that, which when you dive in, there's millions and millions of them, like anything else, I suppose. But there's. I'm thinking, when you're talking about forms, there's a film on Mark by David Rory called Sunday Night Poets, and there's one of the interview sections in which the director is asking, mark, you know, why are you excited about poetry slams? And this goes back to the mid to late nineties, when he makes the film, and Mark jumps on it right away and says, I'm really interested in creating new forms. So there's a long history of international exchange with poetry slam, but you're a prime example for what is even a further extension of slam in a new form, which would be fun and wonderful to hear about Atlanta. So what are two voices? And tell us a little bit about your background.

[00:02:21] Speaker B: Yeah, let's start. Well, we could start.

[00:02:23] Speaker A: Who are you?

[00:02:24] Speaker C: Yeah, this is a very difficult question.

Philosophers know well, my name is Elena Rafisco, and I'm from Sicily in the south of Italy.

In 2017, I started performing slum poetry in Pisa, where I was studying for my baez and the effect on the audience, the connection that people built for these events was absolutely surprising and wonderful. We didn't expect that. I can remember that the very first time I organized a poetry slam scene. The technician asked us, how many seats should I put? And we were like, I don't know. Well, if all our friends come, it can be like 30, 35. But the result was that 120 people showed up and there was no room in the little theater for everybody who wanted to come to listen to poetry. So this was my start, poetry slam. And for me it was a big source of freedom, because I had the feeling that in Italy, and most of all, in academic endeavour, we have this idea that poetry is something sacred, something difficult that you don't really understand, even if you study the same author, the same poet for years and years. Instead, I think that poetry Islam gave me, yes, the freedom of just going on stage and say the thing, say.

[00:04:12] Speaker B: What I needed to say prior to finding it. Were you studying literature?

[00:04:17] Speaker C: I was studying writing literature.

[00:04:18] Speaker B: Yeah, yeah, tell a little bit about that. The lead up to discovering the slam, you were in school when this happened?

[00:04:27] Speaker C: I was at the beginning of my university path. So my BA in Italian is called Triennale. Three years, the first three years. And yeah, I had a classical education because we have this institution that is called the lice. Our high school is about learning Latin and Greek. And so having this idea that literature is something you can conquer through study, you know, not something that is affordable for everyone. It's something, it's for the elite who has the instruments, the tools, the right tools to go through the text and really understand it.

There's this idea that there is a real understanding of a poem and understanding that is too much superficial, that is not worth for other people. And there was something that didn't work for me about that.

[00:05:26] Speaker B: And you said you started the slam, but what was the first? Did you read about slam poetry or did you go to somebody else's show?

[00:05:36] Speaker C: This is a very fun story.

[00:05:38] Speaker B: That's what we're looking for. If it ain't fun, we don't have it on the pocket. Well, we tried.

[00:05:45] Speaker C: Well, I was in Sicily, my hometown, for Christmas, and I was with some friends playing cards. And this friend of mine, that is one of my friends, that is most far from poetry I can say, showed me this video on YouTube of button poetry. There was this performer, Sabrina Benaim, of what it was a slam performance.

[00:06:13] Speaker B: Okay.

[00:06:14] Speaker C: By Sabrina Benheim.

[00:06:15] Speaker B: Okay, okay.

[00:06:17] Speaker C: In Baton Poetry channel. And she had something like 9 million, 9 million views and it was like, oh, my God, poetry on the Internet. What are we doing? This word is completely corrupted.

The vendor. Ma finire, signora mia. We will say in Italian. And I was like, okay, yeah, let me have a look. 9 million views showed me something, you know? And I absolutely loved the poem that was explaining my depression to my mother. This is the title. And then I went through all this baton poetry channel and felt more and more interested. Interested. Then I discovered that there was, in Italy too, italian poetry slam leak on the web. And I texted the Facebook page and asking them, well, I live in Pisa, it's a university city. I think that people would be interested in events like that, in poetry. Maybe you could organize something here. I can help if you need it. And the president of italian poetry, Islam League back then, that was Sergio Garau.

[00:07:36] Speaker B: Okay. Oh, Sergio. Yes.

[00:07:38] Speaker A: You know Sergio?

[00:07:39] Speaker B: Yes, Sergio. He's a great guy. And what he is a crazy performer.

[00:07:43] Speaker C: He said, well, sure, it would be absolutely wonderful to organize in Pisa, but we don't have someone in place, you know, to get in contact with the clubs or the theaters or whatever. So why would. Wouldn't you do that?

[00:08:00] Speaker B: There you go.

Kind of follows attritionist. Because this, as we've talked about it, gets passed on like this. And I know Sergio, so I'm sure he was very helpful because that's part of the definition that if somebody comes to you. Yeah, yeah.

And of course he got you to do it too.

[00:08:21] Speaker C: But I've never seen one. No problem. We send you an emcee from Florence. That was Nicolas Cugnal back then. And then, yeah. With my other colleague, Marco Virgo Ione. We started the scene in Pisa and then we came in touch with all the other scenes that were about born in that years that were like 2017, 2018. All the collectives in the north of Italy were starting their activity.

[00:08:52] Speaker B: Right.

As we talked earlier in the other episode, Lelo Voca was the guy that 2001. He was at the head. I think he was at the head. Roma Poesia was part of it too. That was a big festival in Rome. They actually started the first international slam competition. But I think Lelo was the instrumental thing. He was my contact. I might have a little screwed up.

[00:09:18] Speaker C: I think he had a contact with Arnoldo de Campos.

[00:09:21] Speaker B: Okay, good. So. So that was 2001 and you discovered in 20, 1617?

Yeah, it's the typical slam story. You get word and then why don't you do that call up and the other people that have already done it, you know, make it happen for you. So does the show still go on that you're wanted? Pisa?

[00:09:43] Speaker C: Well, I left Pisa two, three years ago, so now I'm organizing events wherever I live, actually, Sicily, in my hometown, or in the towns nearby, or in Switzerland when I was in Switzerland.

[00:10:00] Speaker B: Oh, that's right. Did somebody pick up your show at Pisa?

[00:10:03] Speaker C: Not for now.

[00:10:04] Speaker B: Okay.

[00:10:04] Speaker C: Not for now.

[00:10:05] Speaker B: Okay.

[00:10:06] Speaker C: But the shows are growing up very quickly. Yeah. I think this year is the year in which we have the greatest number of competitions for the slam championship.

[00:10:20] Speaker B: Yeah. Domi and Famanza, who's another great organizer, has written a great book about Slam. He said that last time I was there, he said that, you know, slam, sometimes it dips down, but now it's at that kind of a second birth thing where it's expanding. Yeah, after Covid.

[00:10:39] Speaker A: So your experience is like, have you traveled outside of Italy then, in addition to the US?

[00:10:43] Speaker C: I traveled a lot in Europe. Yeah.

[00:10:45] Speaker A: And is there kind of a common saying about slam, or what are some thoughts going into these different slams? What are expectations? What are people thinking?

[00:10:54] Speaker C: Well, there's a european political Slam championship that varies location, dedication of the meeting, annual meeting every year. And I've seen the movements in Finland that is very still performance, you know, very polite performance.

While we in Italy, we are more like, we have more movement and, yeah, we use the voice at very high volume. And also, of course, it depends on the location and on the kind of event, but I think that italian performance are renowned for their energy.

[00:11:37] Speaker B: Well, Alessandro. Alessandro is studying in University of Chicago, too. He's from Italy. I first met him before Eleonora. He interviewed me, and he was interviewing me the other day for himself. And he said, well, how would you describe the italian? You know, I said, exuberance. Exuberance.

[00:12:00] Speaker C: Yeah, yeah, yeah, that's true.

[00:12:01] Speaker A: This is a tradition, too, which is interesting to me. We kind of veer to slam to get away from the academy a little bit. And the academy is like this, this great evil thing, but nobody wants to be associated. There's one of the us poet laureates was Donald hall. He was highly regarded in the states. And I used to write letters back and forth to him, and I kept calling him an academic poet because that's how we had created the divisions. Finally, in one of his letters, he wrote back, he goes, I only taught at the university for four years. You know, I think of myself as a poet, not an academic poet.

[00:12:34] Speaker C: Yeah.

[00:12:35] Speaker A: Which was an interesting eye opener for me when you got interested in poetry slam in 2017. But now you're here back kind of in the university, like in the States, it doesn't get any bigger than the University of Chicago. That is the egghead school. It's, you know, U of C versus Harvard. They go back and forth. So what would draw someone to go back?

[00:12:56] Speaker C: Well, my idea is that, that academia is not always as evil as it can seem. I mean, yeah, Harold Bloom, the famous scholar of the influence of the fear of influence, the western canon. Yeah, yeah. That slumpetry was deaf.

[00:13:16] Speaker B: Who?

[00:13:16] Speaker A: They are the deaf. Yeah, yeah.

[00:13:18] Speaker C: So it was a very strong and severe statement, as we can hear many in the academia. But I think that now there is a new vibe inside the scholarship and a new interest. And also, how do we know, what are the artists, what are the poets worth to be read in 100 years or in 1000 years? I mean, academia has a very strong power in signing that together with education at school, because the poets we study at school are the poets we remember that will become the classics of the future. And also, of course, publishing houses. So my idea was, and ease with my PhD project, to leave traces of what is worth remembering of Islam poetry today. And also, I think that sometimes the quality of the performance and also the skills of the performers are taken for granted. And it's not like this in academia. Now there is this very big debate about how should we study performance poetry. We can't use the same tools we are accustomed to use to study poetry on paper, because it's a completely different thing.

You can simply do a physiological work or only focus on words, because the word of per se is not enough, is how the word is delivered to the audience. What are the strategies, the intention behind. And of course, performance poetry shares with theater this ephemerality that is very, is the power, I think, of performance, but also the big danger of losing all the stuff that was meaningful. And people in the future, but also in the present, should be able to share, especially now that technology allows us to find new ways to register, archive, and remember, here at University of Chicago, I took this class that is called mapping black social dance. And the idea was, how can we build an archive on black culture movements like the birth of the house music here in Chicago, it was something a counterculture like Sloan poetry was that were in the basement of people that wanted just to.

[00:15:54] Speaker A: In 2017 in Italy, was slam poetry counterculture. And is it still?

[00:16:00] Speaker C: It was. It was. Now we have progressive mediatization of slam poetry. So more and more, our best performer performers go on television to perform naive poems or to talk about the performance poetry scene. And also with my work and the work of Alessandro in the academia, there's some kind of institutionalization of the movement. Of course, not everybody in Italy already know what slum poetry is. So you go around and sometimes you still need to explain. But there's a progressive interest of the national papers and television that I think will help making the movements known widely. Of course, the danger of this is the homologation of institutional language. Yeah, yeah. But there is a resistance, I think that the community is the most powerful thing of the italian Islam movement. And the community is really crazy. I mean, there are people that don't want to be a poet as a job, as a way of living. They just want to share whatever, share the freedom. Share the freedom of going up on stage and I be something you can't be in real life. This is the power.

[00:17:28] Speaker A: Now, you performed at the Green Mill Jazz lounge here in Chicago, the uptown poetry slam.

[00:17:33] Speaker D: So that's the original one.

[00:17:34] Speaker A: The original one, right.

How was that?

[00:17:37] Speaker B: And then, well, first of all, we should explain that.

So she was here. She told me she was coming to Chicago. And I suggested when we talked in Monza that, you know, you're here, and Alessandro, you told me he was here, that maybe we'll try out the one poetic voice stuff. And as we've talked about before, one poetic voice is where we take one language and get a translation, and then we present the poem in two languages at once, using all the technique that we've discovered from ensemble work in Chicago. We applied that to the one poetic voice stuff. And so you get a performances where both languages are going at the same time and it becomes satisfying for an audience that speaks one of the other languages. It's not literal translation, it's a whole new thing. It becomes a whole new presentation. Keeping faith with the intent of the original text, of what it intended to communicate and its intellectual end and its emotional end. We don't tamper with that, but we don't get stuck in the literal translation of poetry, because that it's impossible anyhow. I mean, anybody will tell you that it's impossible.

[00:18:56] Speaker C: Absolutely.

[00:18:57] Speaker B: And so, you know, I worked. I had to go to, as I think we talked about last episode that I had, I went to France to do collective work, teaching a workshop with the french poets while they were here. So I didn't have a lot of time, so I started them off and showed them some technique. And then Ryan Doyle and Annie Carol from Chicago worked with Alessandro and Eleanor while I was gone. And they did a great job. Why don't you tell us about that experience, the whole experience, because I think that's important too.

[00:19:32] Speaker C: Yeah, absolutely. Well, the main way that is used in the SLA movement, as far as I saw, is to have the text projected behind the back of the poet. That's how the international competition are held.

But the feeling that it's not enough, as we said before about.

[00:19:54] Speaker B: Yeah, the original thing, which started in Italy, was they have a big screen and they put the text, the text, only the text. So you're watching it in one language, performed, but then you're reading the other thing and it's.

[00:20:08] Speaker A: Now here's an origin story, and this relates to this originally, when they start scoring the slams at the national poetry slam level here in America, they had arguments about half of the vote should be about the writing and half of it should be about voting.

[00:20:22] Speaker C: We still say that sometimes.

[00:20:23] Speaker A: Yeah, yeah, we don't do that here anymore. Yeah, but that sounds like that's trying to play.

[00:20:30] Speaker C: Yeah, we still say that in Italy that half of your judgment is about the text and about the performance. Of course, we also say that as emcees or people who take the score, we won't know if you only concentrate on focus on the text or if you only appreciate the performance.

It's your score. And this is the most powerful thing about poetry. It's your vision of the poem. It doesn't care. It doesn't matter if you.

[00:21:01] Speaker A: No, that was beautifully said.

[00:21:02] Speaker C: If you studied poetry or not, if you are a pro in literature or not, or in performance, if you liked it, it's fine.

[00:21:11] Speaker A: So how did you find taking your vision of the poem to the form that is, the two voices that you're.

[00:21:18] Speaker C: Well, it was very interesting experience.

I worked mainly with Andy Carroll, with whom I found a very great connection from the beginning. So we spoke a lot about what does it mean that for you, what do you want to say with this word and what is the most direct way to say the same thing in my language? So we changed a lot. The translation I produced at the very beginning and also when I translate my poems, first of all, I do translate my poems even in English, even though it's not a renowned practice, because the best thing will be mother tongue speaker, to translate the poem in Zhong language. But I prefer to do that and then to have it revised by slammers, by slum poets, because I know they will keep an eye on the rhythm, on rhymes, the internal rhymes.

And this is one of the most difficult part of the translation.

[00:22:23] Speaker A: The two voices, then you and Andy Carroll are doing the same poem, but in, like, explain to me what the two voices are.

[00:22:32] Speaker C: The two voices are fragments, I will say, of a vision or a poem. That is a vision. The main thing was to communicate the feeling that was behind, not behind, was exposed in the poem.

[00:22:55] Speaker B: But it's the one poem.

She translated one of Andy's poems. Yeah, and she had a translation of her poem. So she did. Andy's poem translated Italian, and then one of Zur's was translated to English. So it's the one poem, and the two voices are communicating. Not exactly the same text, but they're communicating the theme, the sense, the feeling, the intent of the text.

[00:23:29] Speaker C: It's a dialogue for different techniques that mark showed us, like lapping. So this idea of going right after the other, as in a run, or as if you were running after the other performer to take the same tempo, the same rhythm. And also. Yeah, we switched a lot. English, the order. English, Italian, Italian, English. And tried to also interrupt the original rhythm of the verse. I even interrupted the verse in the middle because the most important thing was the musicality of the dialogue.

[00:24:07] Speaker A: That sounds very difficult, but there's a.

[00:24:10] Speaker B: Whole set of techniques that we developed. She mentioned a couple of them, but just to go through a few of them, the lap was the one language starts the line, and then the second language starts a little bit into it. And the two are going at once but not synced up. But then we also sometimes sync it up together and try to get the same rhythms happening in English as it's happening in Italian. And then we have swapping stanzas back and the back and forth thing. Also change the moods. One of the poets can be in one mood and the other in another mood, presenting the same text. Yeah, but it gives it a totally different feel, which comes from just regular collective work, that every time you present a poem, you can do it differently. Just as, you know, a jazz musician takes a tune and today he's going to do it angry, or today he's going to do it really soft. It's the same tune.

[00:25:09] Speaker C: Some parts are synced, some parts Andy partner doesn't.

[00:25:12] Speaker B: Yeah. At one point at the mill, Eleanora's word, you know, very exuberant, but Andy is very, oh, kind of calm, and they're saying the same stuff. And the communication is sort of the same communication, but you get different nuances of what it is. Right.

[00:25:34] Speaker C: Yeah, I will say that. And it was the intimate version of my energetic, energetic performance, because, yeah, we have different styles of performance. And, of course, this was the difficult but also most interesting part to put in dialogue our very different ways of. I don't know. For example, I like speaking to the audience directly, looking in the eye. While for any, this is not the best way. So she prefers to go to stand and say the poem to everybody. And so very interesting thing was to make choices. How do you make choices about how do you want to deliver every single word? Every single word. Yeah.

[00:26:19] Speaker A: How did the audience respond at the Green Bay?

[00:26:21] Speaker B: Loved it.

[00:26:23] Speaker C: I have the feeling that it worked. It worked. Yeah, yeah.

[00:26:27] Speaker B: I was a little worried because we didn't have that much time to work on it, to polish it up. It was very enthusiastic. When you mention the choices things.

You talked about this earlier. That's the thing that when you look at performance poetry, like your studies, you were talking about what performance poetry has brought all these new choices into poetry. So you have a. On the. On the page, you have all these choices you can make for the page, but now you have a whole new collective of choices, of communication in performance, the same line can be presented so many different ways, and those are choices. And it's always been my opinion that the more choices that the artist has, the higher he can make his art.

[00:27:18] Speaker C: Yeah, yeah. Be conscious of what you want to do. It is the challenge. Even when you come up on stage, how do you want to come up on stage? Or how do you want to be to show your character or your personality? Because. Because since when your name is called by the MC, the show starts and. Yeah. Having this in mind, it's not easy because you have to become a stage performer. You are in the crowd, mixed up with everybody in the audience, and you are unnoticed in a way. It's not taken for granted that people know you because we are nothing that famous.

When your. Your name is called, then the show starts and you have to be in 100%.

[00:28:09] Speaker B: Right. And we had great fun with Alessandro and Ryan.

Right. Alessandro translated Ryan's poem, I'm a cloud.

[00:28:19] Speaker C: Yeah. Oh, it'll be a cloud to be a cloud.

[00:28:22] Speaker B: So I wasn't sure about whether Alessandro was to go for it, but he was totally it.

I said, well, okay, enter as clouds. So they came up waving their arms around and trying to be the two of them. A cloud coming on stage.

[00:28:40] Speaker C: Yeah. Also, I think that the crowd at the green mill is expecting to be entertained. They expect some variation. You can just do say the poem in a normal way. This not normal way.

[00:28:54] Speaker A: What, from your experience with Mark Smith particularly, and the green mill, are you taking back to Italy with you?

[00:29:01] Speaker C: I'm taking back enthusiasm.

I think that really moves me is while people are performing, looking at Marx and seeing that he's laughing, I can see some sparkling, some sparks, his eyes. This is something that really moves me because I have the feeling that poetry works. When I see that, I have the feeling poetry works. And also the other thing is that gave us instructions you should do that. And sometimes we didn't agree about how certain things should have been done. Finally, the very last thing he said that was, have fun. People want to see poets having fun in what they're doing.

[00:29:47] Speaker A: Poets having fun.

[00:29:48] Speaker C: Yeah. Yeah. It's not about being worried of do the thing. Right. The most important thing is to enjoy what you're doing.

[00:29:56] Speaker A: And what was the title of your piece that you did with the two voices?

[00:30:01] Speaker C: We changed the title, actually, because in Italy, Italian is siriquiele. So you should. But for our performance, we called it don't cry, you.

[00:30:17] Speaker D: Nompiangere condo europeano sempre manche nelsenzo prabrio del pasare delle coze de la cose que pasano dangono apartivicita masensa dupio andranovia dame sono pasti anichi, sono pasti. Amore, sono pasati luagi estena tivia t perduti altricerto.

[00:31:06] Speaker C: Nostalgia.

[00:31:07] Speaker D: Mrs. Perjevadoso dubuankeli eo voluntari di persone luagi felicita di fare pokestore pantare estetilacia losaique sifa trobunal tro da so situamicione perpoi sparire sensa ritokiri campano funeralike.

[00:31:50] Speaker C: In.

[00:31:50] Speaker D: Nature al consumator pagi non legarti men suno puraspetatila fina onikazai unconfina e que alafina mirabello. Yo credo inchoke immortale credo nelarte credo nela capacita dimetre da parte la morte o nitanto. Yo credo nelapoesia una santa provocatoria inconcludente firamente nuti le quindi libera libera quinoi liberi restimo incastrati alenostre ferite limidade finite sensa. Peter felicia secondo solon ayo non pensavo quetanti la morta neves fatima.

[00:33:14] Speaker C: The show mascara.

[00:33:26] Speaker D: Magari rimane.

[00:33:30] Speaker A: So you've given an example about Finland in terms of how their style is what speaks to Italy. And slam poetry specifically?

[00:33:39] Speaker C: Well, it's not easy to find specific from an internal point of view. But I will say we use a lot of words. As Andy many times noticed that I had these very long poems full of words, very hard to memorize. So, yeah, I think I have the feeling that about the rhythm and the time we have the.

We normally use all the time offered. So three minutes. Three minutes and 10 seconds, we do it.

And also me, myself, I speak for myself, I always break this rule of the lamp because I have the feeling that my poems needs to breathe more than the rapidity that is asked. And also, yeah, I will say we sing a lot. So the musicality.

[00:34:39] Speaker B: Oh, that's interesting.

[00:34:40] Speaker C: Yeah. The idea of playing with different volumes of the voice and rhythm and the real singing is something that happens a lot also with the actors that nowadays are more and more implied in the scene. I will say that improvisation is also an element that is important.

Now we have even an improvisation poetry championship because there are a few poets that got some very good skills on that. And people are even interested in workshops about how do you improvise poetry. And of course, Mitali, there's a very important tradition of improvisation in terzarima or otave, taba, toscana, that are structures, but in which you can move. And the structure is very important to improvise because you have something that from which you should start, not blind page.

[00:35:40] Speaker A: And how serious is the competition part taken in Italy?

[00:35:43] Speaker C: It depends. I will say that nowadays is taken a little seriously because we had three portrait slam champions of the curtum organized by pilot Lyot in Paris.

And these took for the performers very good opportunities, like being meted in tv or a tv show or having the possibility to offer their show to theaters and clubs.

[00:36:16] Speaker A: Do you find it ironic that the man that started the slam has downbeat in the competition portion since the start?

[00:36:23] Speaker C: Yeah, yeah.

[00:36:24] Speaker A: It's an ugly head that rears itself all the time in these things, and the master comes and slats the hat off of it.

[00:36:31] Speaker C: I have faith in the community because I can see the silly ideas. Yeah. People still do it because it's something that they enjoy. Yeah.

[00:36:41] Speaker A: Good. That's well said. Thanks so much for being here.

[00:36:44] Speaker C: Thank you. Thank you for having me. Thank you very much, Mark.

[00:36:49] Speaker B: And Mark.

[00:36:50] Speaker C: Yeah, thank you.

[00:36:53] Speaker A: You've been listening to through the mill, our podcast about the poetry slam. My name is Mark Elleveld. I'm the editor of the spoken word revolution books. Emily Kelvo is here with us. She named the podcast. It's an anthology she's been working on since the early nineties. And we're here with Mark Kelly Smith, the founder of Poetry Slam. We're going to be bringing some podcasts and shows to you to hear the origin stories from a bunch of different poets and a bunch of different organizers. Our director Hughes over there in the corner. I hope you had a good time, and we'll talk to you soon.